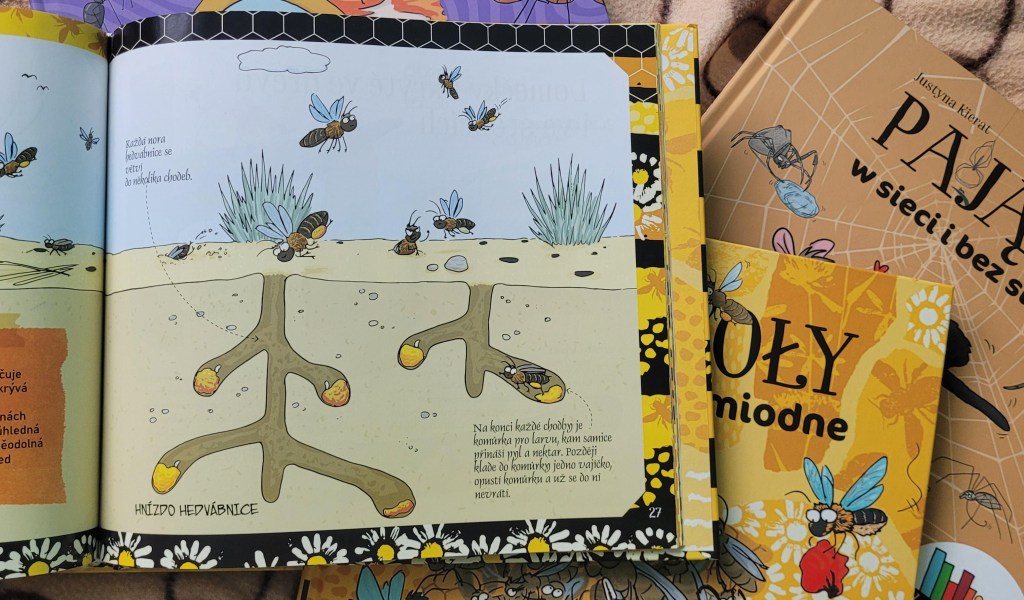

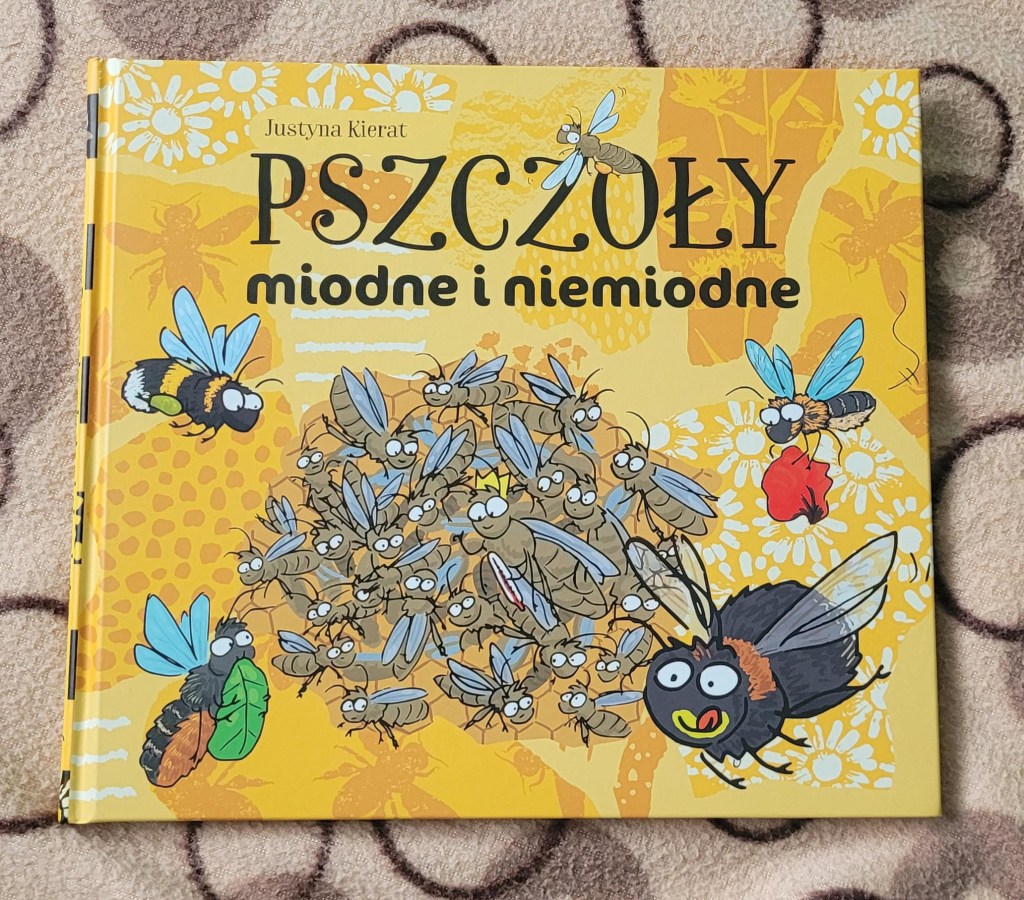

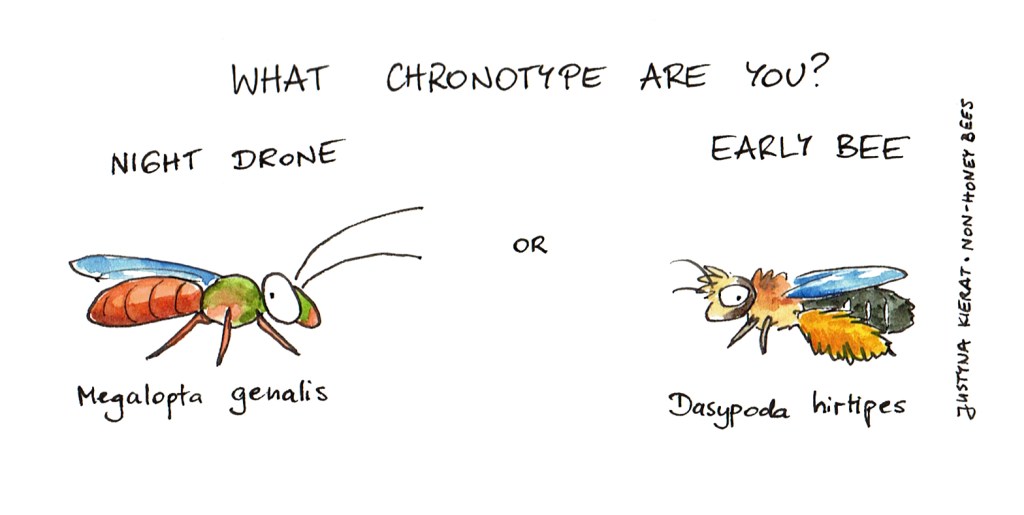

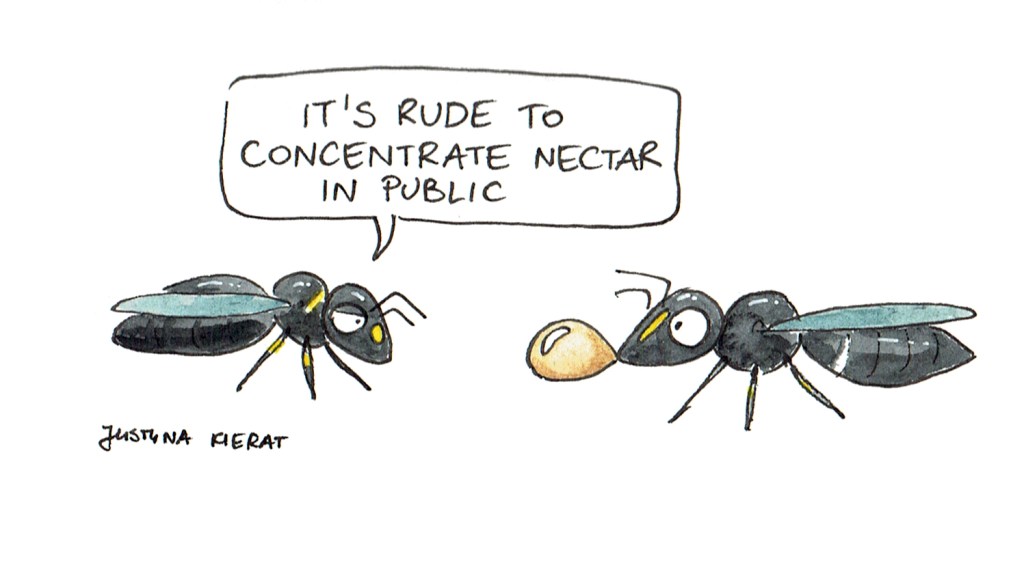

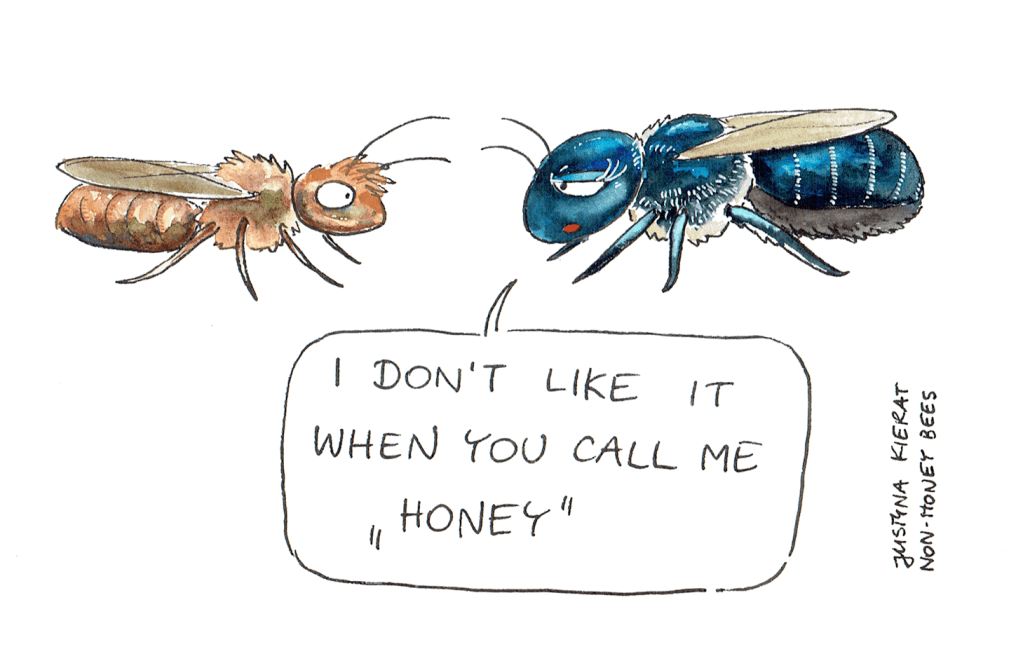

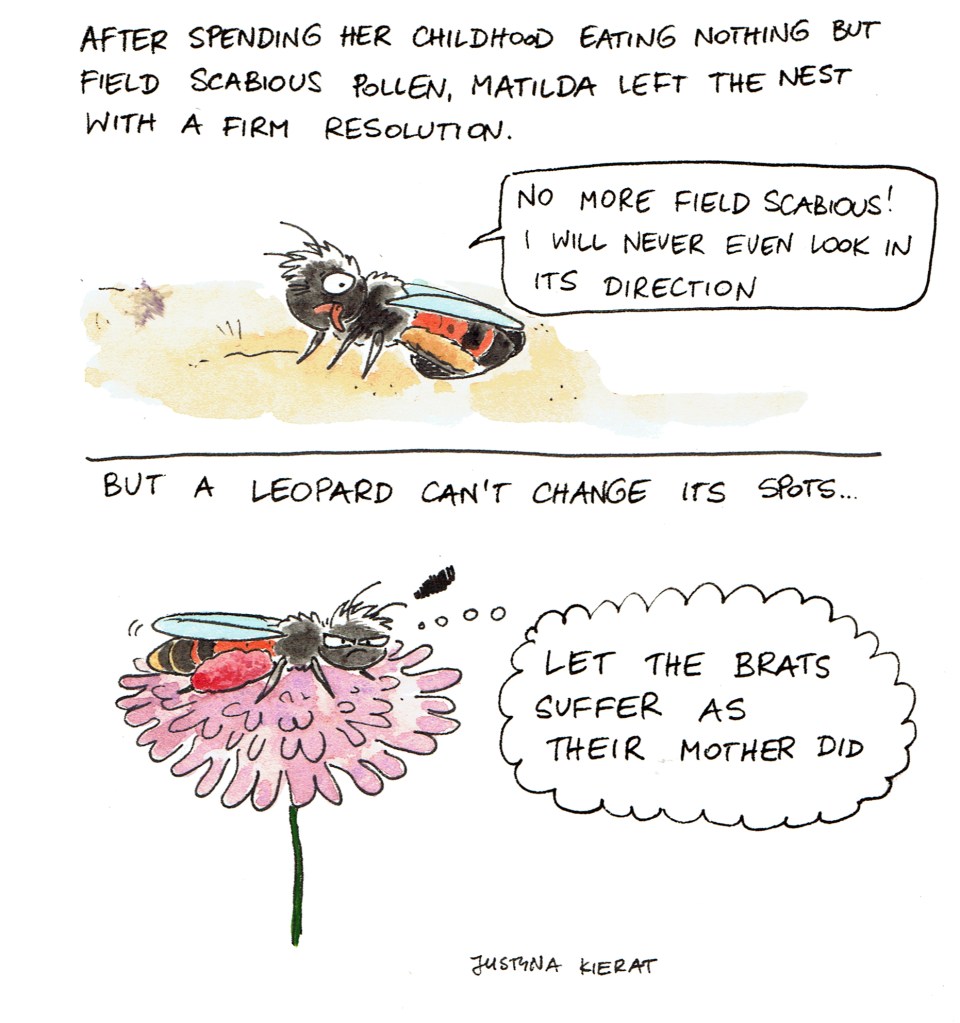

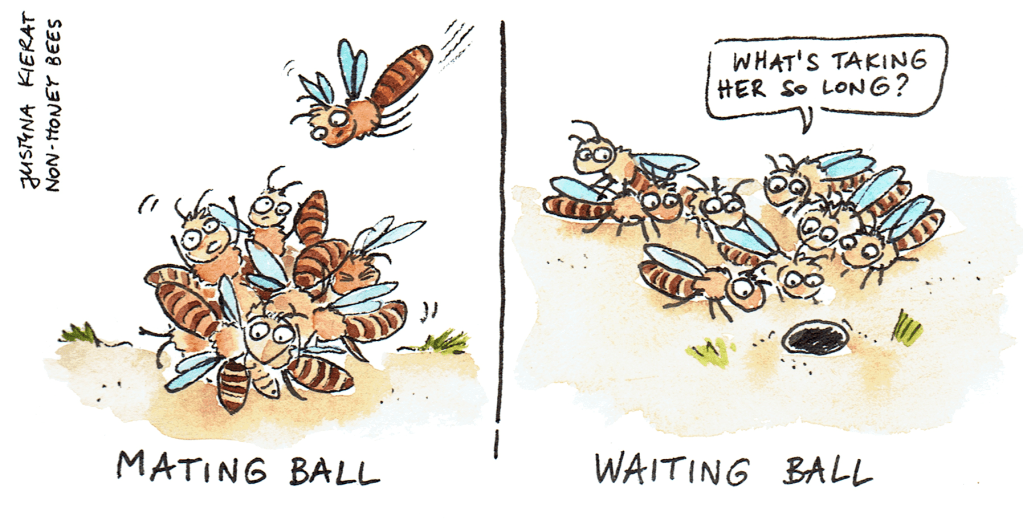

I’ve wanted to show you this for a long time. I’ve finally taken some good photos, so I can do it now. As you might know, I’m a biologist specialising in non-honey bees, an educator, and wildlife illustrator. The yellow books you can see in the photos are the result of combining these three things. The book is called “Honey- and Non-Honey Bees” (well, now you know where this page gets its name from:) ), and it presents the diversity of bee species and their lives. Although my cartoon drawings make it look like a children’s book, it’s not quite so – adults who are not yet familiar with bees can also enjoy it.

The book was originally published in Polish and was later translated into Czech and Slovak. I wish it could be published in more languages, but there’s not much I can do about that. However, if you know of any interested publishers, you can give them the contact details of the Polish publisher that owns the copyright to my book.

The violet and orange book are two more from the series that I wrote and illustrated: one about ants and another about spiders.