Have you heard that bees can’t see the red color? I guess so. Maybe you even read that in some of my posts. Recently, I stumbled upon two papers, one by Chittka and Waser, published in 1997, and a bit more recent one, by Martinez-Harms et al. (2009). And these papers, especially the first one, have shown me that the issue of bee color vision isn’t so black and white (pun intended). Let me explain it a bit below, but I strongly recommend you reading the original papers.

Bees are trichromats, as we are, which means that they have three types of receptors in their eyes, each type sensitive to different light wavelengths. We can see the wavelengths from, basically, violet to red, whereas bees can also see UV, and they are less sensitive to the red part of the spectrum. However, they are not completely blind to red: one of the receptor types is sensitive to wavelengths which humans could well describe as red color. So, a monochromatic red object will not be black to bee.

But then, although bees can see the red light, they seem not to be able to see red as fully distinct color. If you show them monochromatic green, yellow, orange or red light, the bees will perceive them as the same or very similar hues, but they will differ in their brightness. As Chittka and Waser put it, “for example, a monochromatic red light of strong intensity will generate the same sensation as a green light of moderate intensity”. So, you can trick a bee into believing there is no color difference between the two stimuli if you cleverly choose wavelengths and light intensities for them.

But the story doesn’t end here! In real life, bees rarely have to do with monochromatic objects. What an eye perceives as a given color, is usually a mix of different wavelengths. Therefore, it is much less likely that a red flower will so perfectly match a green background that it will be invisible to bees. If it reflects light of some shorter wavelengths in addition to the red ones, it’s easy – a bee can distinguish its colors well. If it reflects only red light, however, she will rely on brightness contrast, which will be a bit more demanding but still possible. It was observed that bees foraging on “truly red” flowers take more time flying between distant inflorescences than between flowers of other colors, probably because locating them is more challenging.

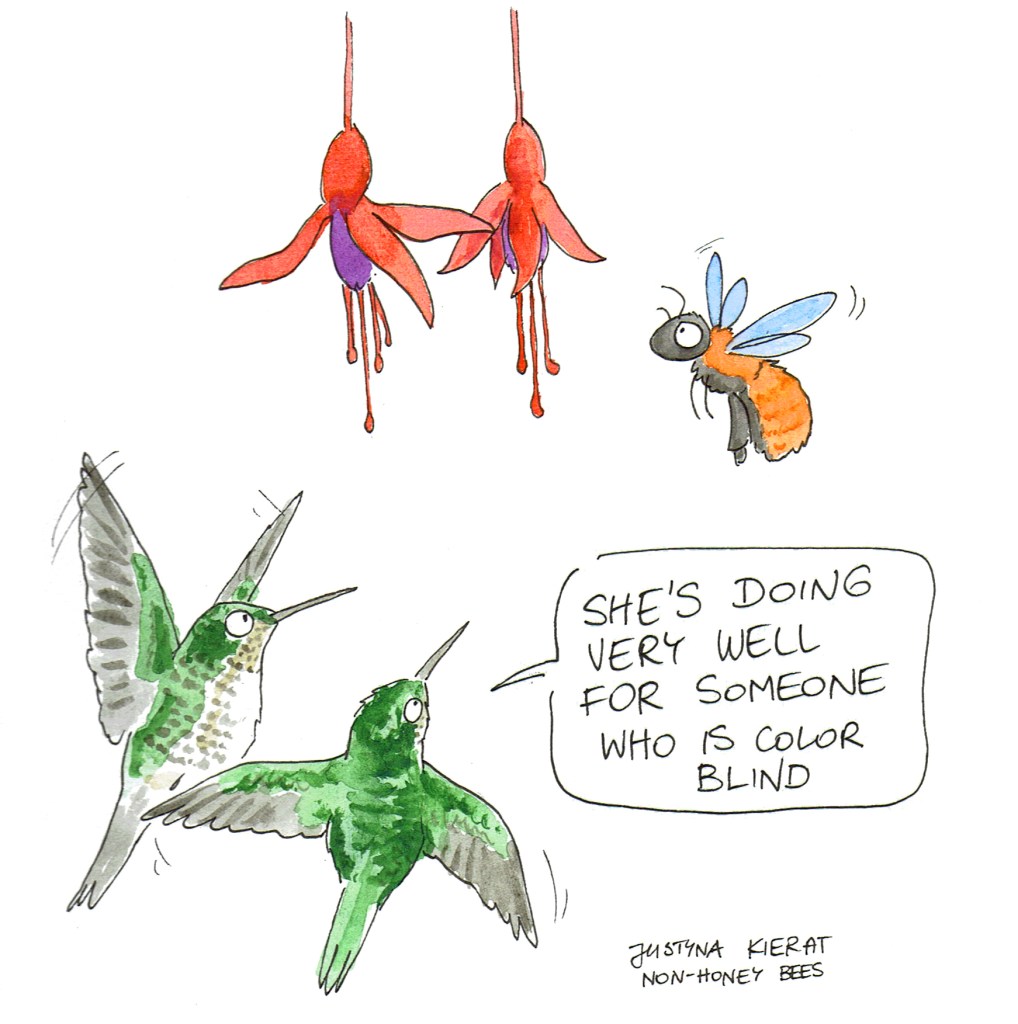

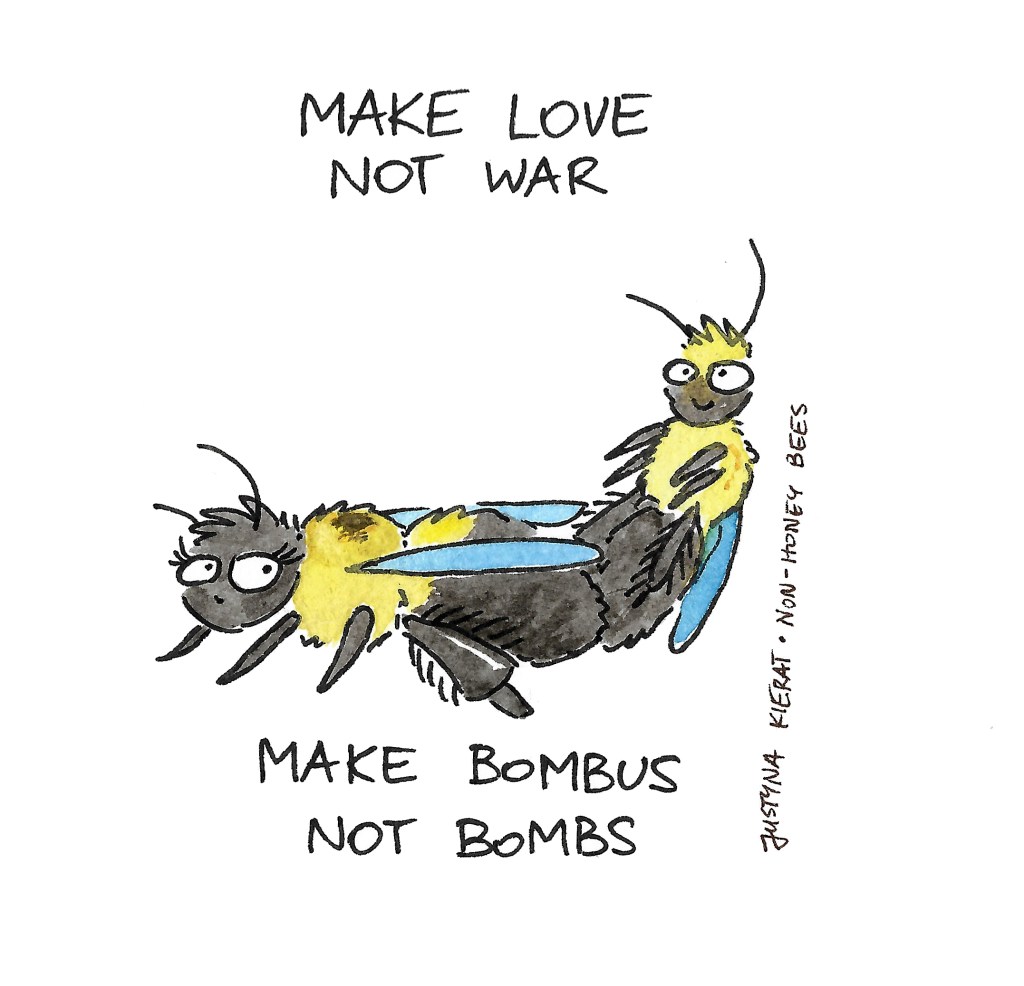

And regarding the cartoon, the hummingbirds are quite justified in speaking about color-blindness of the bumblebee, as their color vision is amazing, better than bees’ and ours. The bumblebee in the cartoon is Bombus dahlbomii, the rare South American species which is known for its love of red flowers.